The 4 Ps of patient experience go beyond being simple frameworks; they act as blueprints for delivering meaningful, patient-centred care that individuals truly recognise and value.

When hospitals equip patients with knowledge, they turn complex clinical processes into engaging experiences, inspiring confidence, building trust, and promoting better long-term health outcomes across diverse populations.

This blog explores three key interpretations of the 4 Ps of patient experience, examining how patient education underpins and enhances each model’s impact effectively.

The Proactive, Personalised, Predictive, and Precise Framework

This model shows how the 4 Ps of patient experience reflect a forward-looking, technology-enabled healthcare approach grounded in proactive prevention, personalised care, predictive analytics, and precise interventions.

- Proactive: Patient education helps patients spot early warning signs and practice preventive strategies. Consequently, they can seek timely medical advice, reduce risks, and improve outcomes.

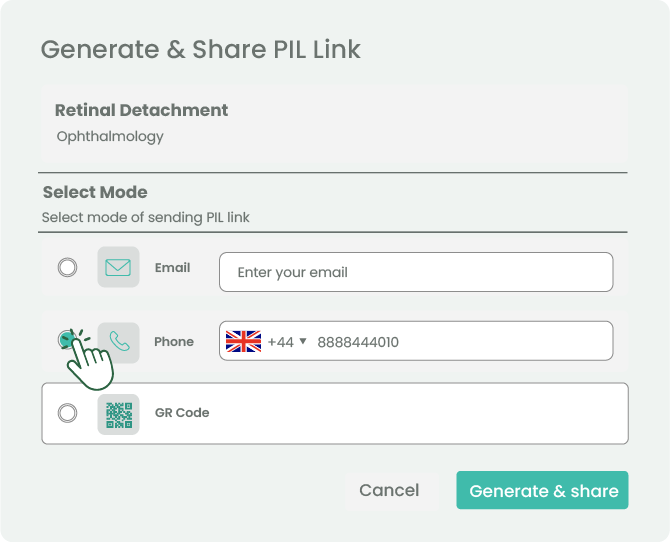

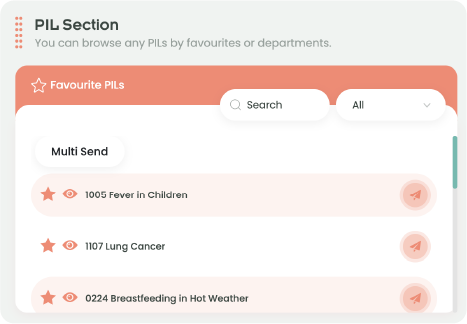

- Personalised: Tailored educational materials match literacy, language, and culture. In turn, they make care relevant and connect treatments to real needs.

- Predictive: Predictive analytics matter only when patients understand their risks. Therefore, accessible education empowers them to act early and live healthier lives.

- Precise: Complex treatments demand understanding. Through education, patients follow regimens safely and manage their conditions confidently.

Ultimately, patient education transforms technology into engagement. It turns data into action, boosts confidence, and enhances every patient’s experience.

The People, Processes, Places, and Patients Framework

This interpretation of the 4 Ps of patient experience highlights the wider healthcare system, showing how education connects people, processes, and places directly to patient needs.

- People: Education improves communication and trust between professionals and patients. As a result, it supports shared decisions and delivers better outcomes.

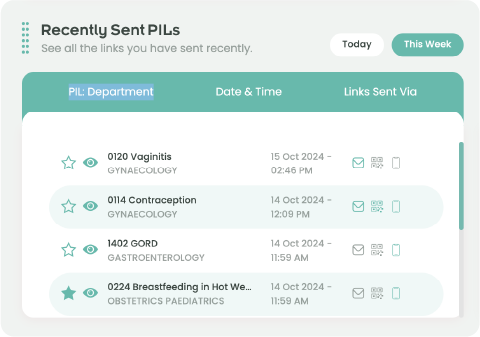

- Processes: Clear, consistent information reduces confusion and anxiety. Moreover, it smooths care pathways and increases compliance.

- Places: Education ensures consistent messages across hospitals, communities, and digital platforms. Therefore, patients feel reassured and experience seamless continuity of care.

- Patients: Knowledge builds confidence. Consequently, educated patients become active partners in managing their own health.

Patient education unifies this model by aligning people, processes, and places with patients’ needs, strengthening patient experience and quality of care across diverse healthcare environments.

The Nursing “4Ps”: Pain, Potty, Position, and Possessions

In contrast, the nursing-focused 4 Ps of patient experience emphasise immediate comfort and safety during purposeful rounding, highlighting the vital role of education in bedside care.

- Pain: Education helps patients describe pain clearly, which leads to faster and more effective management.

- Potty: When patients understand safety risks, they request help promptly, preventing falls and preserving dignity.

- Position:Teaching repositioning reduces pressure injuries and enhances comfort throughout recovery.

- Possessions: Knowing how to use call systems and mobility aids fosters independence and reduces anxiety.

Thus, even bedside checks become opportunities for empowerment, where patient education strengthens comfort, builds trust, and deepens engagement within hospital routines and broader healthcare journeys.

Conclusion

Across all models of the 4 Ps of patient experience, patient education consistently transforms principles into practice. It helps patients anticipate risks, manage conditions, and engage actively with care.

For hospitals, embedding education within these frameworks strengthens outcomes, fosters trust, and demonstrates true excellence in delivering patient-centred healthcare.

Start transforming your patient experience by integrating structured education into your 4 Ps strategy today.

References

- Bandura, A. (1997) Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman.

- Beryl Institute (2016) Defining patient experience. Available at:Berylinstitute (Accessed: 28 September 2025).

- Elwyn, G., Frosch, D., Thomson, R., et al. (2012) ‘Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice’, Journal of General Internal Medicine, 27(10), pp. 1361–1367.

- Epstein, R.M. and Street, R.L. (2011) ‘The values and value of patient-centred care’, Annals of Family Medicine, 9(2), pp. 100–103.

- Flores, M., Glusman, G., Brogaard, K., Price, N.D. and Hood, L. (2013) ‘P4 medicine: how systems medicine will transform the healthcare sector and society’, PerMed, 10(6), pp. 565–576.

- Meade, C.M., Bursell, A.L. and Ketelsen, L. (2006) ‘Effects of nursing rounds on patients’ call light use, satisfaction, and safety’, American Journal of Nursing, 106(9), pp. 58–70.

- NICE (2021) Shared decision making. NICE guideline [NG197]. Available at: NICE (Accessed: 28 September 2025).

- Patient Information Forum (PIF) (2020) PIF TICK: The UK quality mark for trusted health information. Available at: PIFONLINE (Accessed: 28 September 2025).

- Stableford, S. and Mettger, W. (2007) ‘Plain language: a strategic response to the health literacy challenge’, Journal of Public Health Policy, 28(1), pp. 71–93.

- Topol, E. (2019) Deep Medicine: How artificial intelligence can make healthcare human again. New York: Basic Books.

- World Health Organization (2023) Patient engagement and health literacy. Available at: WHO (Accessed: 28 September 2025).